Part 2: A brief overview of the American Civil War.

The Civil War is the central event in America’s historical consciousness. While the Revolution of 1776-1783 created the United States, the Civil War of 1861-1865 determined what kind of nation it would be. The war resolved two fundamental questions left unresolved by the revolution: whether the United States was to be a dissolvable confederation of sovereign states or an indivisible nation with a sovereign national government; and whether this nation, born of a declaration that all men were created with an equal right to liberty, would continue to exist as the largest slaveholding country in the world.

Northern victory in the war preserved the United States as one nation and ended the institution of slavery that had divided the country from its beginning. But these achievements came at the cost of 625,000 lives–nearly as many American soldiers as died in all the other wars in which this country has fought combined. The American Civil War was the largest and most destructive conflict in the Western world between the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815 and the onset of World War I in 1914.

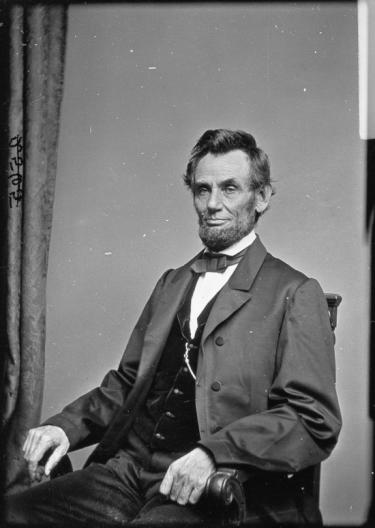

The Civil War started because of uncompromising differences between the free and slave states over the power of the national government to prohibit slavery in the territories that had not yet become states. When Abraham Lincoln won election in 1860 as the first Republican president on a platform pledging to keep slavery out of the territories, seven slave states in the deep South seceded and formed a new nation, the Confederate States of America. The incoming Lincoln administration and most of the Northern people refused to recognize the legitimacy of secession. They feared that it would discredit democracy and create a fatal precedent that would eventually fragment the no-longer United States into several small, squabbling countries.

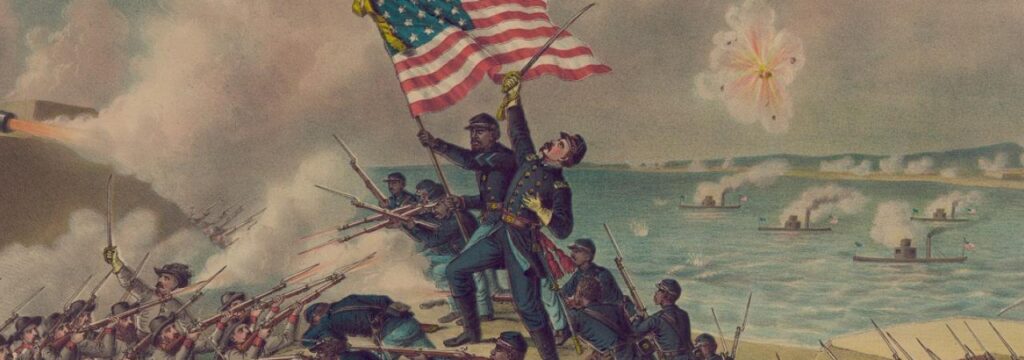

The event that triggered war came at Fort Sumter in Charleston Bay on April 12, 1861. Claiming this United States fort as their own, the Confederate army on that day opened fire on the federal garrison and forced it to lower the American flag in surrender. Lincoln called out the militia to suppress this “insurrection.” Four more slave states seceded and joined the Confederacy. By the end of 1861 nearly a million armed men confronted each other along a line stretching 1200 miles from Virginia to Missouri. Several battles had already taken place–near Manassas Junction in Virginia, in the mountains of western Virginia where Union victories paved the way for creation of the new state of West Virginia, at Wilson’s Creek in Missouri, at Cape Hatteras in North Carolina, and at Port Royal in South Carolina where the Union navy established a base for a blockade to shut off the Confederacy’s access to the outside world.

But the real fighting began in 1862. Huge battles like Shiloh in Tennessee, Gaines’ Mill, Second Manassas, and Fredericksburg in Virginia, and Antietam in Maryland foreshadowed even bigger campaigns and battles in subsequent years, from Gettysburg in Pennsylvania to Vicksburg on the Mississippi to Chickamauga and Atlanta in Georgia. By 1864 the original Northern goal of a limited war to restore the Union had given way to a new strategy of “total war” to destroy the Old South and its basic institution of slavery and to give the restored Union a “new birth of freedom,” as President Lincoln put it in his address at Gettysburg to dedicate a cemetery for Union soldiers killed in the battle there.

For three long years, from 1862 to 1865, Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia staved off invasions and attacks by the Union Army of the Potomac commanded by a series of ineffective generals until Ulysses S. Grant came to Virginia from the Western theatre to become general in chief of all Union armies in 1864. After bloody battles at places with names like The Wilderness, Spotsylvania, Cold Harbour, and Petersburg, Grant finally brought Lee to bay at Appomattox in April 1865. In the meantime Union armies and river fleets in the theatre of war comprising the slave states west of the Appalachian Mountain chain won a long series of victories over Confederate armies commanded by hapless or unlucky Confederate generals. In 1864-1865 General William Tecumseh Sherman led his army deep into the Confederate heartland of Georgia and South Carolina, destroying their economic infrastructure while General George Thomas virtually destroyed the Confederacy’s Army of Tennessee at the battle of Nashville.

By the spring of 1865 all the principal Confederate armies surrendered, and when Union cavalry captured the fleeing Confederate President Jefferson Davis in Georgia on May 10, 1865, resistance collapsed and the war ended. The long, painful process of rebuilding a united nation free of slavery began.